Encouraging pupils to read is hugely important. Getting students reading historical fiction is a great idea as Marc blogged about a wee while back. It will help them develop their sense of period and will allow them to build their knowledge of key events in history.

More importantly, though, if we can recommend the right books more students may be encouraged to read simply for the pure joy of it.

One book to recommend if your classes study the Russian Revolution at any level is the new novel by Theresa Breslin: The Rasputin Dagger.

One book to recommend if your classes study the Russian Revolution at any level is the new novel by Theresa Breslin: The Rasputin Dagger.

Exclusively for History Resource Cupboard, Carnegie Medal-Winner, Theresa Breslin, has written a short blog about her latest novel aimed at youngsters.

Background

The Rasputin Dagger is set in Russia with the action moving between Petrograd (now St Petersburg) and Yekaterinburg in Siberia.

The story starts in 1916 – the year before the outbreak of revolution in Russia – and follows the two main characters, Nina and Stefan until 1918 – the year of the murder of the Imperial family.

The backgrounds of these two young people are vastly different, yet chance throws them together, and, as civil unrest deepens and a bitter Russian winter closes in, the Revolution threatens not only their love but their very lives.

Synopsis

Russia 1916: A country on the brink of Revolution.

Nina Ivanovna’s uneventful life in a village in Siberia is suddenly shattered. She flees to Petrograd / St Petersburg, taking with her a carved oblong box which contains a strangely powerful dagger. Unknown to her she is being pursued.

Stefan Kolodin – young and idealistic – is a medical student at the University of St Petersburg. Driven by his own demons, he wants change for Russia and its people.

Amidst the chaos of a city in revolt, their lives collide. And a stormy relationship develops… full of passion and dangerous politics.

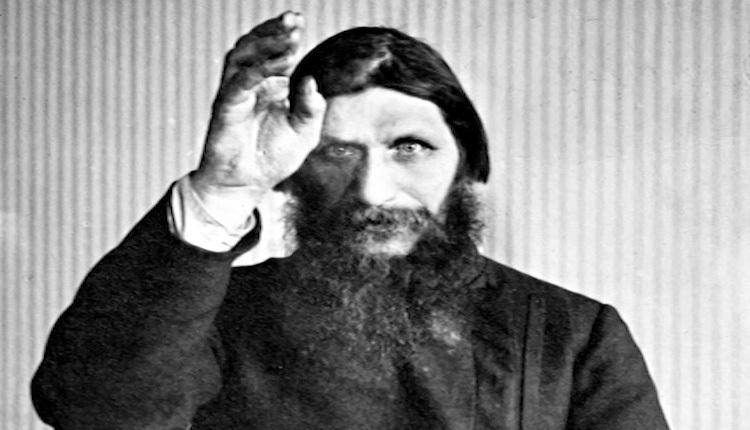

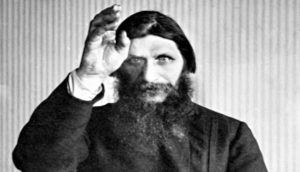

While Stefan risks his life and career to support rebellion and struggles to help the wounded soldiers returning from the battlefields, Nina is drawn into the lavish lives of the Royal Family and begins to fall under the spell of their mysterious monk, Grigory Rasputin.

While Stefan risks his life and career to support rebellion and struggles to help the wounded soldiers returning from the battlefields, Nina is drawn into the lavish lives of the Royal Family and begins to fall under the spell of their mysterious monk, Grigory Rasputin.

The ruby studded dagger Rasputin owns is, chillingly, a mirror image of the one left to Nina by her father.

And it carries a deadly curse.

About the Author

A Carnegie Medal-Winner, Theresa Breslin is a popular, multi -award winning author, critically acclaimed for over 50 books, with work dramatised on stage, TV and radio.

She writes for all age groups and is renowned for the depth of the research in her historical novels, which includes Remembrance, her top selling tale of youth in WWI.

While writing The Rasputin Dagger Theresa did research by reading letters and witness accounts of events, studying texts and localised information, such as weather reports. She also visited St Petersburg and Siberia to produce an immensely readable story with resonance and relevance for today.

Historical Background from Theresa

There were in fact TWO revolutions in Russia in 1917. The first, (the February Revolution) at the beginning of the year, was sparked off largely due to the protest organized by the women of Petrograd / St Petersburg which forced the abdication of the Tsar and the formation of a ‘Provisional’ Government of the people.

The second revolution (the October Revolution) took place at the latter end of the year when Lenin led the armed branch of the Bolshevik Political Party to overthrow the new Provisional Government and seize complete control.

At the time of the Revolution, the Romanov family had ruled Russia for centuries with sole authority, only allowing a token people’s assembly called the Duma which had no real power.

When World War One broke out Russia fought on the side of the Allies. Their army was poorly equipped and suffered colossal loss of life. Homeless refugees flooded into the cities, food was scarce, and many people died of starvation or the intense cold. The Tsar, who had taken over as Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces was blamed for this.

There was also terrible tension within his own household because the Imperial Crown had to be inherited by a male heir, and their only son (now aged twelve), had the debilitating condition of haemophilia.

The arrival of a supposed faith-healer, a monk called Grigory Rasputin, seemed at first to help the situation, and the family came to rely heavily on him for emotional support. But Rasputin increasingly interfered in their lives, giving foolish political advice. Other members of the Imperial Family, Ministers of State and many of the general public grew to hate Rasputin.

The winter of 1916 was exceptionally harsh resulting in an escalating death toll at home and on the battlefields. In December of that year Rasputin was brutally killed in strange and suspicious circumstances. Despite restrictions, more meetings and protests took place and popular political parties grew in strength.

At the beginning of 1917, on International Women’s Day (23rd Feb, Old Calendar), the women in Petrograd took to the streets to protest about the lack of bread. Over the next few days they were joined by factory, office and transport workers which brought the city to a standstill. Large sections of the armed forces refused to fire upon the crowds who would not disperse.

Faced with increased mutinies Tsar Nicholas II abdicated at the beginning of March, and a Provisional Government was formed. In October 1917 the Bolsheviks, acting decisively and with force, overthrew the Provisional Government. Was it a bungled incompetent event or a highly organised act? This enquiry gets you to heart of the October Revolution with your students.

Thereafter the Bolsheviks suppressed opposition and defeated the forces trying to reinstate the rule of the Tsar.

In 1918 the Imperial Family, the Tsar, his wife and five children were murdered. History Resource Cupboard’s enquiry on should History Department’s spend money on Lenin artefacts indirectly gives an overview of the period 1917-24.